Week 8: Madden-Julian oscillation#

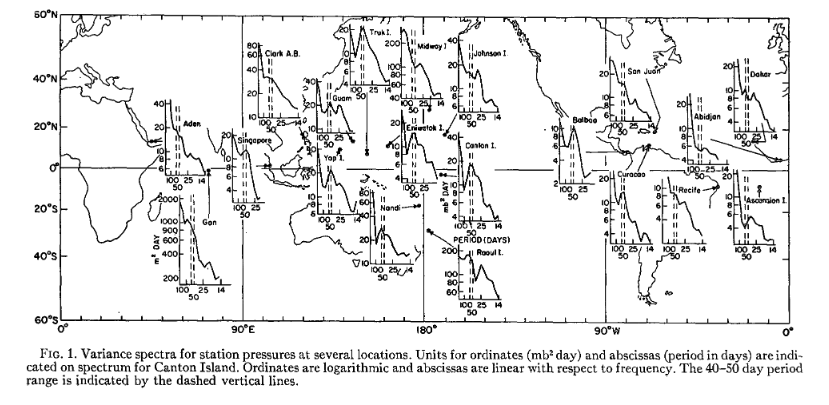

The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) is a distinctive phenomenon that occurs in the tropical Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific. It is characterized by large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns (with zonal wave numbers ranging from 1 to 4) and operates on intraseasonal timescales, lasting between 20 to 90 days. Due to its intraseasonal nature, it is often referred to as tropical intraseasonal variability. The MJO’s signal is so strong that it can even be detected in raw-sounding data and water vapor channels. Fig. 20 below illustrate the power spectrum of tropical sea-level pressure from various sounding stations , as presented in the [MJ71] paper. A notable peak around 40-50 days is a clear indicator of the MJO. Also, Fig. 21 shows an observed MJO event located at the western Pacific from unfiltered column water vapor.

Fig. 20 The power spectrum of tropical intraseasonal variability#

Fig. 21 The total precipitable water of an MJO event in Indian ocean from MIMIC-TPW.#

The MJO has significant global effects. It plays a key role in modulating the variability of the summer monsoon in South and Southeast Asia, influencing related extreme events such as tropical cyclones and droughts. Additionally, its interaction with the subtropical jet stream can generate quasi-stationary Rossby waves, allowing wave energy to propagate toward North America, creating the Pacific-North America (PNA) pattern. This, in turn, impacts winter storms and the polar vortex. Despite the considerable global influence of the MJO, modeling its dynamics has posed challenges for the scientific community since its discovery. Two critical aspects in understanding the MJO are its (1) frequency (or period) and (2) the evolution of its vertical structure from shallow to deep convection. We will explore these various characteristics and examine how they affect the ability to accurately model the MJO.

Theories for MJO#

wave perspective#

Two primary theories have been developed to explain the MJO: (1) wave dynamics and (2) the moisture mode framework. Each theory addresses different physical thresholds. Regarding wave dynamics, notable contributions were made in the 1990s by Dr. Bin Wang, Dr. Tim Li, and C.-P. Chang (from our department). The wave dynamics theory, often referred to as the wave school, originates from the shallow water equations, where the influence of gravity and Rossby waves is significant. For example:

in (65) \(\text{Div}\), \(\zeta\) and \(\phi_p\) represent the divergence, vorticity, and temperature, respectively. The tendency terms in these equations have magnitudes similar to other terms, such as advection, indicating that the inertial effects are still significant. This suggests the system has not yet reached a full dynamical equilibrium, and wave processes continue to play a role. Additionally, diabatic heating is governed by the vertical redistribution of moisture, similar to the convective instability of the second kind (CISK).

moisture mode framework#

In the moisture mode framework, the assumption is that the internal adjustment of gravity waves has already reached equilibrium, leading to the removal of \(\frac{\partial \text{Div}}{\partial t}\) from the system. Furthermore, under the weak temperature gradient approximation, the third equation simplifies as follows:

A key distinction in the moisture mode framework is that the forcing is considered a prognostic variable rather than a diagnostic one. This means that the forcing evolves over time, rather than being predetermined. From the comparison between (65) and (66), we can see that the treatment of both the internal wave processes and the forcing mechanism is crucial.

It’s important to note that these two frameworks represent opposite ends of the parameter spectrum, with one being more wave-like and the other more akin to moist static energy (MSE) variability. A substantial amount of tropical variability lies somewhere between these two perspectives.

Some Evidence from Wave Dynamics Perspective#

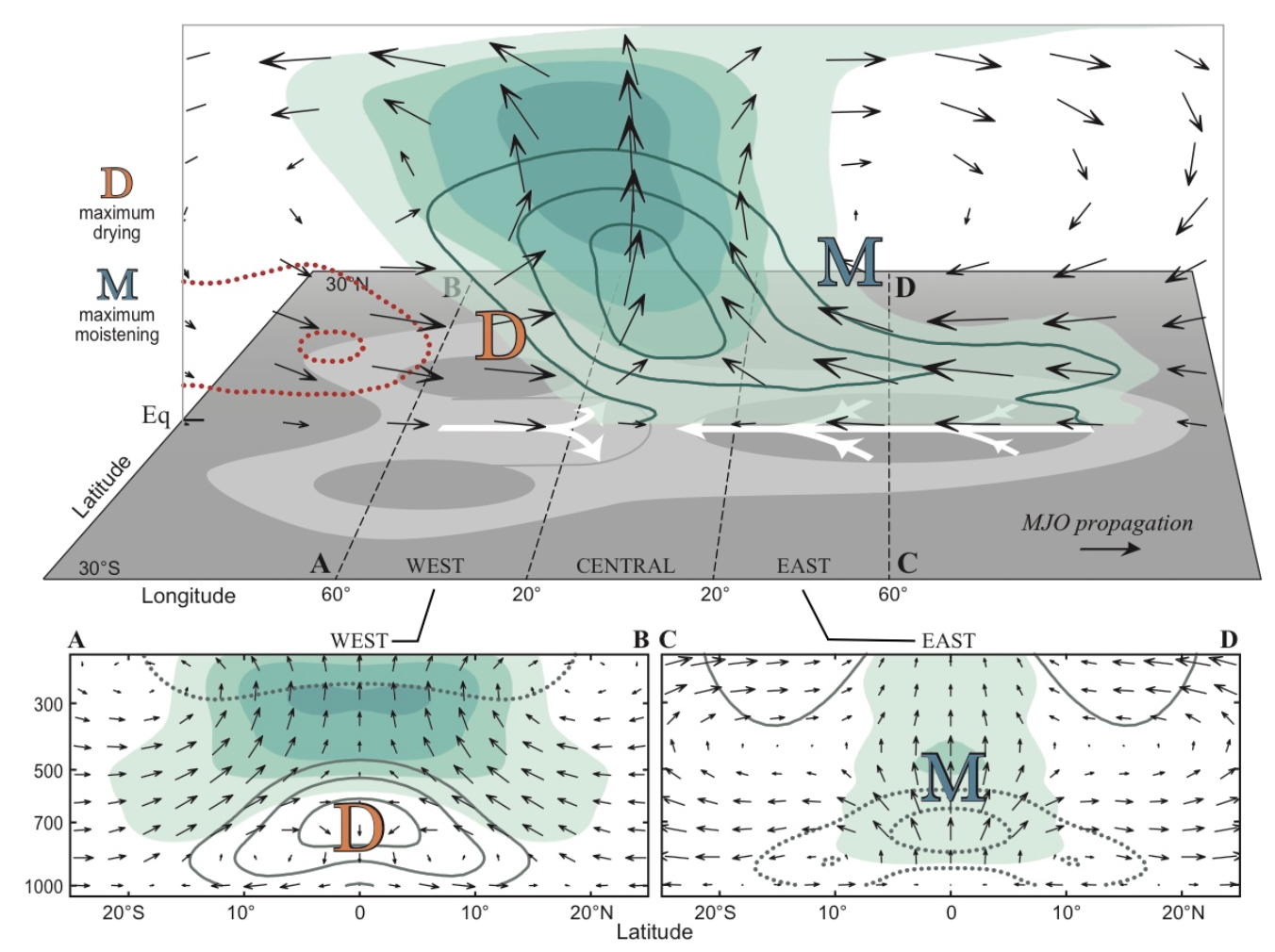

From the perspective of wave dynamics, the MJO has long been regarded as a type of convectively coupled wave for several reasons. First, the circulation pattern associated with the MJO closely resembles that of a forced Kelvin wave, where the horizontal winds exhibit a Gill-like response (which we will explore in more detail later). Specifically, there are easterly winds to the east of the convection and westerly winds to the west. The eastern portion of the MJO shows similarities to observed convectively coupled Kelvin waves, while the western part is often characterized by twin cyclones. Moreover, the easterly phase is associated with shallower circulation (and lower cloud heights), while the westerly phase is linked to stratiform clouds, featuring a top-heavy heating profile.

The shallow circulation aids in recharging moist entropy into the free troposphere through shallow divergent flow, which exports lower dry static energy but imports moist-laden air from the boundary layer. Conversely, deep circulation efficiently discharges moist entropy from the column to other regions. This recharge-discharge process of column energy is crucial to MJO dynamics, as it directly influences the intensity and distribution of diabatic heating. This aspect has been largely absent from traditional wave dynamics theories (or more focus on the recharge of DSE from wave dynamics perspective). We will delve deeper into this topic when discussing the Gill solution.

The vertical structure of the MJO, which tilts from east to west, strongly resembles the structure observed in equatorial Kelvin waves. In tropical wave theory, the presence of shallow circulation can be explained by momentum balance within a frictional planetary boundary layer. Upward motion at the top of this boundary layer induces shallow heating (around the 4th baroclinic mode), which in turn slows the propagation speed. During the convective phase, the maximum upward motion near 300 hPa, coupled with divergence in the upper troposphere, creates a first baroclinic mode structure. This process allows the column to export energy, which accelerates the propagation speed. The coupling between shallow and deep heating profiles results in a wave speed that falls between these two modes. However, even with shallow heating factored in, the phase speed remains faster than what is observed.

Fig. 22 The vertical structure of MJO and the cross-section at westerly/easterly phase. From [AW15]#

The boundary layer momentum balance#

In the boundary layer, the momentum equation can be written as

where the subscript B represents boundary layer. One should notice that we don’t include the thermodynamics equation in the boundary layer equation given that the diabatic processes associated with shallow cumulus is weaker those those found in the free troposphere (not a perfect but workable assumption). Another important feature is that the boundary and lower free troposphere share the same pressure gradient, which can be attributed to the fast adjustment in the planetary boundary. Leveraging the same assumption (fast adjustment) for scale analysis, we can also drop the tendency term due to the fast adjustment, leading to

(68) is a diagnostic equation, i.e., as long as we know the pressure gradient force in the free troposphere, we know \(u_B\) and \(v_B\) in the boundary layer. The boundary layer in turn feedback to the free troposphere through (47) (\(\tilde{w}\)). The shallow vertical motion can trigger shallow mode of heating and recharge the column MSE.

From (68) we also know the steady motion of boundary layer convergence on an equatorial beta plane can be written as

In large-scale motion (where the pressure gradient is small), the second term is the dominant forcing where the lower-troposphere westerly/esterly is characterized by boundary layer top convergence/divergence. Such boundary-top convergence/divergence will further lead to the downward/upward motion in the lower troposphere. In the off-equatorial region, Severdrup balance (negative planetary PV advection balanced by stretching) is the main cause of the lower-troposphere vertical motion.

One key take-home message is that the boundary-layer top easterly collocated with boundary ascending motion, which is a quarter phase leading the mid-troposphere ascending motion. Thus, as long as the surface friction exists, we can always see such phase difference between the boundary layer ascending motion and the mid-troposhere ascending motion.

Note

Severdrup balance has also been applied to explain the stationary Rossby wave response such as the monsoon-desert mechanism proposed by Dr. Brian Hoskins back in 1980s. See [RH96]

Lidzen-Nigam Model (optional reading)#

In the previous subsection, we show that the boundary convergence/divergence is determined through 3 processes. (1) pressure gradient force at the top of boundary layer (2) Ekman pumping and (3) Sverdrup balance. However, all three processes are controls from the lower free troposphere. The lower boundary i.e., SST, on the other hand, also plays a role in the boundary layer convergence. Lidzen-Nigam model (Lidzen and Nigam 1987) is one of the few model exploring the contribution of SST.

In Lidzen-Nigam model, we have a balanced momentum equation on a sphere.

Similar to (68), (70) is a diagnostic equation, indicating that as long as we have the information of pressure gradient force, we know the convergence within the boundary layer.

Different from (68), we would like to link such pressure gradient force to the surface temperature. To achieve that, one can integrate the hydrostatic equation vertically, i.e., \(\int_{p_s}^{p_T}dp=\int_{z_s}^{z_T}-\rho g dz\). Given the Bousinessq approximation is solid in the boundary layer, the density change can be directly attributed to the change in temperature. i.e.,

Also, given the 3-D boundary layer temperature as a function of surface temperature, we have

where \(\alpha\) is the lapse rate of zonal mean temperature (~3K/km) and \(1-\gamma\frac{z}{H_0}\) is the decaying rate of the eddy temperature, which is about 0.7 from surface to trade-wind inversion (PBL top). The surface temperature has two components (1) zonal mean and (2) eddy. The eddy component decays faster than the zonal mean temperature due to the weak temperature gradient in the free troposphere.

Substituting (72) and (71) back into (70), one can easily diagnose the boundary convergence. Readers will find that the meridional SST gradient plays the dominant role in determining the boundary layer convergence as long as the pressure gradient at the boundary layer top is small. This is especially the case for Eastern Pacific ITCZ and the boreal winter ITCZ at Indian ocean. (see Lidzen and Nigam 1987 for more details)

Some Evidence from Moisture Mode Perspective#

Three necessary conditions for a moisture mode variability happens, (1) the diabatic heating is dominated by the moisture-related processes (2) weak temperature gradient (3) Precipitation anomaly is highly correlated with moisture anomaly.

According to these criteria, there are evidences supporting the moisture mode framework, especially over the Indo-Pacific regions. First, the weak temperature gradient approximation (i.e., \(w\frac{N^2}{g}=\frac{Q}{c_p T}\) is a good approximation on intraseasonal timescales (even a more solid approximation than applying it to wave time scales). This indicates that the dynamics are nearly in a state of equilibrium. Second, the moistening/drying in the lower troposphere (\(\sim\)700-hPa) has an equivalent contribution to the residual of the column process (i.e., vertical moisture advection balanced by the physical processes), suggesting what happens in horizontal directions is equally important. Precipitation anomaly is in generally highly correlated to column moisture if it’s linearized in intraseasonal timescales.

Overall, MJO has satisfied all three criteria in the region of the Indian Ocean, and it meets either one or two criteria over other basins. Details can be found in XXX.

Gill Solution (the forced and steady state wave solution)#

The Gill solution is a steady state, forced response of the wave solution. To acquire the steady-state wave solution, we adopt (52)

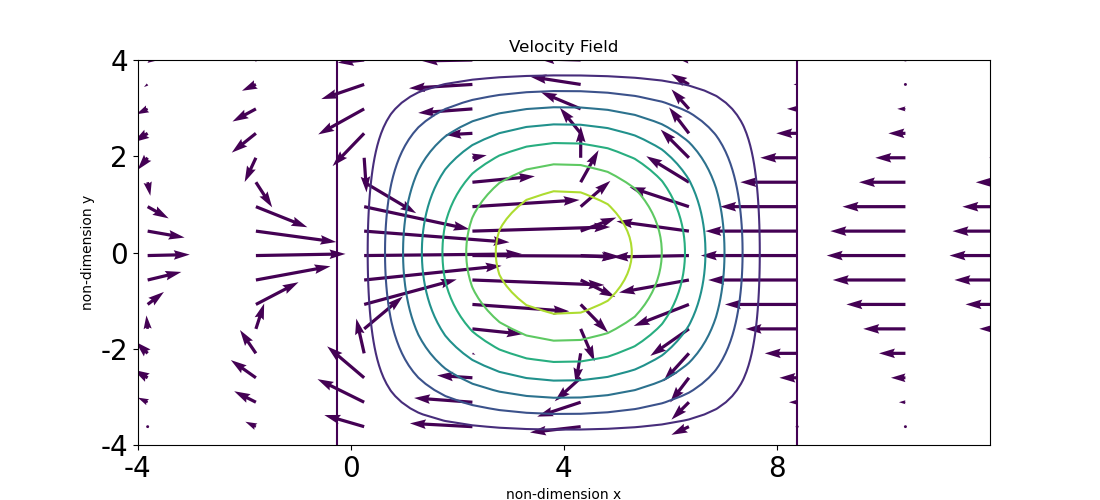

where \(W_m(p)\) is the eigen basis of vertical normal mode decomposition and \(Q_{m}\) is the coefficient of the corresponding vertical mode. (see (61)). Thus, the first step to solve Gill solution is decomposing the diabatic heating into various normal modes, where each mode corresponds to different equivalent depths (gravity wave speed). Then, the derived coefficients (i.e., \(Q_m\) in the third equation of (73)) of each mode are functions of longitude and latitude, which will be used to solve the horizontal wave solution (i.e., the first 3 equations in (73)). In Gill (1980), he employed variable transformation to solve the analytical solution of a Gaussian-like heating on the equator. To the west of the heating shows a twin-cyclone and to the east of the heating is characterized by a Kelvin wave-like feature.

Fig. 23 Gill solution. Contours are prescribed heating patterns and vectors show the circulation driven by heating.#

Gill’s solution has been applied to explain the observed circulation on a beta plane with a resting basic state. Some real-world cases include the monsoon-desert relationship, MJO circulation, and North American low-level jet. In addition, it’s the backbone of the moisture mode framework. In moisture mode, heating is dominated by the variation of moisture, which is redistributed by circulation. The circulation can further be diagnosed using Gill solution.

Following the discussion in the first week, one can find that the moisture mode starts from an energetic perspective and emphasizes on the role of moisture in determining the intraseasonal variation of moist static energy. Thus, the intrinsic timescales of moisture mode variability is determined by the redistribution of MSE rather than the adjustment of DSE.

More details can be found in [AK16].

Gross Moist Stability and Gross Moist Stratification#

The last important concept in moisture theory is the Gross Moist Stability. The gross moist stability was originally proposed by Neelin and Held (1987), which describes the gross effect of convection in redistributing column moist static energy. It starts from the dry and moist static energy equations

where \(F^{R}\), \(F^{S}\) and \(F^{LH}\) are fluxes of radiation, dry static energy (s), and latent energy respectively. \(-Q_{LH}\) is the latent heating due to the transition from water vapor to cloud liquid water. Combining the dry static energy equation with the moisture equation, we have the prognostic equation of MSE (m). The column-integrated m can therefore be written as

While the observed tropical circulation is dominated by the first baroclinic structure (divergence in the upper layer and convergence in the lower layer or vice versa), we have the following relationship

where the first equation of (75) indicates the nature of mass continuity in the first baroclinic structure. \(m_2\) and \(m_1\) are the vertical velocity weighted (mass flux i.e., the integration of divergence) moist static energy in the lower and the upper layers. (equivalent to cumulus ensemble in Yanai et al. 1973). In a steady state, (76) leads to

where the overline is time mean and prime is the transient components. The disappearance of \(\overline{F_B^{S}}\) indicates there is no sensible heat transport at the tropopause. In the convective regions, the main balance happens \(-\Delta \overline{s} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim L\overline{P}\), while in clear sky region \(-\Delta \overline{s} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim \overline{F_B^{R}}+\overline{F_B^{S}}-\overline{F_T^{R}}\). One can find that the static stability plays a role in \(\Delta \overline{s}\) since it represents the vertical difference in dry static energy. Similar balance happens in moisture budget, where in convective regions: \(-\Delta \overline{q} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim L\overline{P}\) and in other regions \(-\Delta \overline{q} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim \overline{P}+E\). The problem is \(-\Delta \overline{q} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim \overline{P}\) as well as \(-\Delta \overline{s} \nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}} \sim L\overline{P}\) are not viable equations given that they don’t link convergence or precipitation to the boundary forcing (i.e., not a predictive theory). Thus, the small flux terms at the boundary must be retained to form a predictive theory through averaging a wider domain i.e.,

(78) says that the vertical transport of moist energy static energy is mainly balanced by the difference in flux at the top and the bottom of the column. Through this, we can have a simple diagnostic equation for convergence.

The term \({\Delta \overline{m}} \) or \(\Delta \overline{s}-Lq_2\) is so-called gross moist stability. It is defined as the weighted moist static energy by vertical velocity and take the difference between upper layer and the lower layer (kind of similar to static stability but take the effect of convective heating into account). Physically, it quantifies how much of the column energy can be exported through the unit convergence/divergence. i.e., \({\Delta \overline{m}} \sim \frac{\overline{F_B}-\overline{F_T}}{-\nabla \cdot \overline{\mathbf{V_2}}} \) . A similar equation can be found in the moisture budget, so-called gross moist stratification.

Back to the moisture mode framework (i.e., (66)), the gross moist stability/stratification states how efficient it is for convection to redistribute (export) the column MSE or moisture. The reason why vertical structure matters is that \({\Delta \overline{m}}\) is column weighted (by vertical velocity), thus, different vertical structures of convection can lead to different efficiencies of MSE transport. Details can also be found in the discussion of [AK16].

Á F Adames and D Kim. The MJO as a dispersive, convectively coupled moisture wave: theory and observations. J. Atmos. Sci., 2016.

Ángel F Adames and John M Wallace. Three-dimensional structure and evolution of the moisture field in the MJO. J. Atmos. Sci., 72(10):3733–3754, October 2015.

David S Battisti and Anthony C Hirst. Interannual variability in a tropical atmosphere–ocean model: influence of the basic state, ocean geometry and nonlinearity. J. Atmos. Sci., 46(12):1687–1712, June 1989.

J Bjerknes. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial pacific1. Mon. Weather Rev., 97(3):163–172, March 1969.

James R Holton and Richard S Lindzen. An updated theory for the quasi-biennial cycle of the tropical stratosphere. J. Atmos. Sci., 29(6):1076–1080, September 1972.

Fei-Fei Jin. An equatorial ocean recharge paradigm for ENSO. part I: conceptual model. J. Atmos. Sci., 54(7):811–829, April 1997.

Yi-Xian Li, J David Neelin, Yi-Hung Kuo, Huang-Hsiung Hsu, and Jia-Yuh Yu. How close are leading tropical tropospheric temperature perturbations to those under convective quasi equilibrium? J. Atmos. Sci., 79(9):2307–2321, September 2022.

Richard S Lindzen and James R Holton. A theory of the quasi-biennial oscillation. J. Atmos. Sci., 25(6):1095–1107, November 1968.

Roland A Madden and Paul R Julian. Detection of a 40-50 day oscillation in the zonal wind in the tropical pacific. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 28:702–708, July 1971.

Taroh Matsuno. Quasi-geostrophic motions in the equatorial area. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan, 44(1):25–43, 1966.

Julian P McCreary, Jr. A model of tropical ocean-atmosphere interaction. Mon. Weather Rev., 111(2):370–387, February 1983.

Mark J Rodwell and Brian J Hoskins. Monsoons and the dynamics of deserts. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 122(534):1385–1404, July 1996.

Stephen E Zebiak and Mark A Cane. A model el niñ–southern oscillation. Mon. Weather Rev., 115(10):2262–2278, October 1987.