Week 6 and 7: Tropical Wave Theory#

Shallow Water Model#

Aside from the zonal mean circulation, eddies significantly influence tropical climatology. We refer to the results from Week 2 and 3: Scale Analysis in this section for the discussion of this week. In a hydrostatic, and low-latitude atmosphere (weak temperature gradient), the governing equation can be written as.

By integrating the third equation from the surface (or the boundary top) to the interface \(\eta\) (refer to Fig. 15) and using the reduced gravity concept from (18), we can rewrite (44).

Here, \(\eta\) represents the interface location (see (18)), and \(w(z)\) denotes the rate of displacement change, expressed as \(\frac{d \eta}{dt}\).

Furthermore, based on quasi-equilibrium principles, we understand that diabatic heating and cooling are counterbalanced by the adiabatic cooling and heating from vertical motion, as indicated by (20). Consequently, a forcing term can be introduced into the final equation, expressed as:

This uses the geopotential height to rewrite the previous equation. The last line of (46) shows that diabatic heating-driven vertical motion almost balances horizontal flow convergence/divergence. This applies to both external (with unreduced gravity) and internal modes (with reduced gravity).

Note

It’s important to note that \(w_0\) in (45) isn’t necessarily zero. For non-normal flow at the lower boundary, we need \(w(x, y, z = h_B, t) = u\frac{\partial h_B}{\partial x} + v\frac{\partial h_B}{\partial y}\), assuming \(\frac{\partial h_B}{\partial t} = 0\) at the boundary. This results in:

(47) shows that normal velocity arises from two processes: (1) momentum advection of \(h_B\) by \(u\) and \(v\), and (2) mass convergence/divergence at \(h_B\).

To simplify (46) into an internal wave equation, we can calculate the difference between two vertical layers, introducing a counteracting force from the upper fluid. Alternatively, a more useful form of the final equation in (46) is:

Here, \(\phi_p = -\alpha\), \(\omega = \overline{\rho} g w\), and \(\sigma = \frac{R}{p \rho g} (\Gamma_d - \Gamma) = \frac{N^2}{\rho^2 g^2} = \frac{C_0}{p^2}\), where \(C_0\) is the external gravity wave speed. (48) represents the hydrostatic thermodynamic equation, derived by rewriting \(d \mathrm{ln}\theta\) from (5) with \(\frac{c_p}{R} \mathrm{ln}\alpha\). This form makes it easier to solve vertical motion since pressure velocity weighting is already factored in.

Conservation of Shallow Water PV#

(45) also conserves potential vorticity. To demonstrate this, we can take the curl of the first equation, resulting in:

The last equation of (49) indicates that the rate of change in absolute vorticity is proportional to the rate of change in height, implying that \(\frac{d}{dt}\left( \frac{\zeta + f}{\eta} \right) = 0\). (Note that the expression derived in the final equation of (45) imposes a stricter constraint on potential vorticity conservation.) Furthermore, {eq}shallow_water_4 can also be derived from (45) using the Kelvin circulation theorem (homework).

Equatorial Wave Equations#

Although (45) is significantly simplified, it remains unsolvable due to its nonlinear nature. To address this, we can begin with a linear approximation or assume a resting basic state (\(u = \overline{u} + u'\) where \(\overline{u}\) is independent of time, or \(\overline{u} = 0\) for a resting basic state) with a boundary condition of \(w_0 = 0\). This simplifies the equations as follows:

where \(g'\eta = C_0^2\), with \(C_0\) representing the gravity wave speed. This set of equations is the well-known formulation derived by Matsuno (1966) and is a solvable system.

As (50) contains four unknowns and four equations, it is inherently solvable. Additionally, the equation has a separable form, allowing us to assume a solution of the form \(u, v, \phi = {\widehat{u}, \widehat{v}, \widehat{\phi}}(x, y, t) \frac{dW(p)}{dp}\) and \(w = \widehat{w}(x, y, t) W(p)\) to separate the horizontal and vertical structures. Substituting this back into (50), we obtain:

Rearranging the last equation of (51) as \(\frac{d^2 W}{dp^2} / \frac{W}{p^2} = -\frac{C_0^2 \omega}{\widehat{\phi'}}\), the left-hand side is solely a function of pressure, while the right-hand side depends only on \((x, y, t)\). This leads to \(\frac{d^2 W}{dp^2} / \frac{W}{p^2} = -\frac{C_0^2 \omega}{\widehat{\phi'}} = -\lambda\). According to Sturm-Liouville theory, \(\lambda\) represents a series of distinct integers (i.e., \(\lambda = 1, 2, 3\)). We can rewrite \(\lambda\) as \(\frac{C_0^2}{C^2}\), so that \(C^2 = \frac{C_0^2}{\lambda}\).

Note

While linearizing (45) significantly simplifies the problem, it introduces limitations. The linear momentum equation prevents the energy cascade into new scales (i.e., it does not capture the filamentary structure of vorticity). This feature is crucial for redistributing moisture in the lower troposphere.

With the separation of variables, we can rewrite the governing equations as:

Here, the first three equations describe the horizontal structure, while the last equation describes the vertical structure, making both sets of equations solvable. We will begin by solving for the horizontal structure, followed by a discussion of the vertical structure.

Horizontal Wave Solutions#

To further simplify the problem, we can non-dimensionalize each variable by introducing non-dimensional parameters:

Here, the superscript \(\text{non}\) indicates the non-dimensional variable. With this scaling, we can isolate the independent parameters, and the resulting equations can be written as follows (for simplicity, the superscripts are dropped):

One advantage of using this non-dimensional form is its broad applicability to different parameter spaces. For instance, as long as the shallow water assumption holds, this set of equations remains valid regardless of the Rossby number. We can further simplify by assuming a separable structure for the meridional and zonal components of the waves:

Substituting (55) back into (54) and eliminating terms involving \(U(y)\) and \(\Phi(y)\), we derive a differential equation that describes the meridional structure of tropical waves:

We can solve this equation by applying the boundary condition that \(V(y)\) tapers off to zero as \(y \to \pm \infty\) and assume \(V(y)=\widehat{V(y)}e^{-y^2}\). This assumption can convert (56) into a typical Hermite differential equation, where \(\widehat{V(y)}=H_m(y)\) is so-called Hermite polynomial.

Another special case arises when we use the long-wave approximation (where \(v\) vanishes due to the wave’s length being so large that the zonal boundaries, where meridional winds occur, are negligible in a limited domain). This leads to:

The corresponding differential equation is:

Equations (56) and (58) yield two distinct dispersion relationships where the wave amplitude is conserved along characteristic lines:

Note that the negative sign in the first equation is unphysical due to certain constraints (this is an exercise left for the reader). The term \(2m+1\) in the second equation is derived from Sturm-Liouville theory.

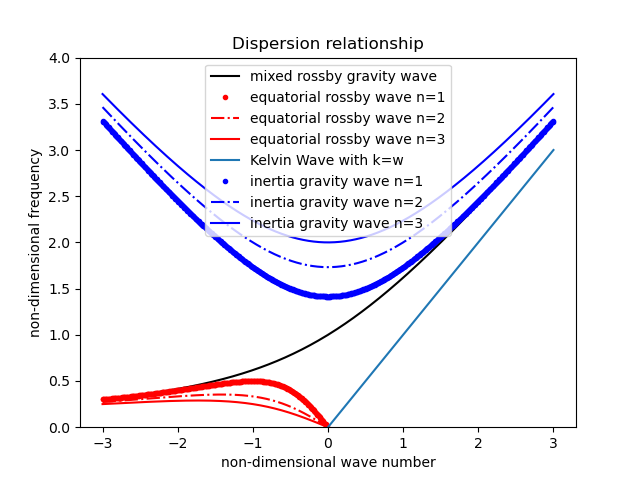

Looking at (59), we see that the first equation is non-dispersive (i.e., the wavelength does not affect the wave propagation speed). This represents a pure gravity wave, which can be proven by calculating the potential vorticity in (57) (another exercise for the reader). The second equation can be broken down into three distinct regimes: (1) Rossby wave-dominated, (2) gravity wave-dominated, and (3) mixed regimes.

Case 1: Rossby wave regime#

In this case, the dominant balance is \(-k^2-\frac{k}{\omega} \approx 2m+1\), meaning \(\omega\) is small. Therefore, \(\omega \approx -\frac{k}{k^2+2m+1}\), similar to the result from the barotropic vorticity equation. This regime represents the low-frequency limit (i.e., the time scales dominated by the Earth’s rotation)

Case 2: Inertia-gravity wave regime#

Here, \(\omega^2-k^2 \approx 2m+1\), meaning \(\omega\) is large. In this case, \(\omega = \pm \sqrt{k^2+2m+1}\). For large \(k\) (larger than \(2m+1\) but about the same scale of \(\omega\)), \(\omega \approx \pm k\), indicating the wave is dominated by gravity wave propagation. The reader can continue the analysis for small \(k\) and will find it slightly tilting westward due to the existence of \(2m+1\), indicating this wave can still feel the rotation of the earth given its planetary scale circulation.

Case 3: Mixed Rossby-gravity wave (Yanai wave)#

A special case occurs when \(m=0\), leading to the simplified dispersion relation \((\omega+k)(\omega^2+k\omega-1)=0\). The three roots are \(\omega=-k\), \(\omega = \frac{k}{2}+\sqrt{\left(\frac{k}{2}\right)^2+1}\), and \(\omega = \frac{k}{2}-\sqrt{\left(\frac{k}{2}\right)^2+1}\). The root \(\omega=-k\) behaves like a gravity wave, while the other two can be categorized into three cases (eastward propagation, westward propagation with small \(k\), and westward propagation with large \(k\)). In the eastward-propagating case, it tapers toward the inertia gravity wave’s dispersion relationship. In low wave number to westward propagating cases, it behaves like a Rossby wave. Therefore, this special case is called mixed Rossby-gravity wave, which has the characters of both waves. In the real world, MRG is an important embryo for cyclone genesis.

These three cases are summarized and shown in the figure below.

Fig. 16 The dispersion relationship of tropical waves.#

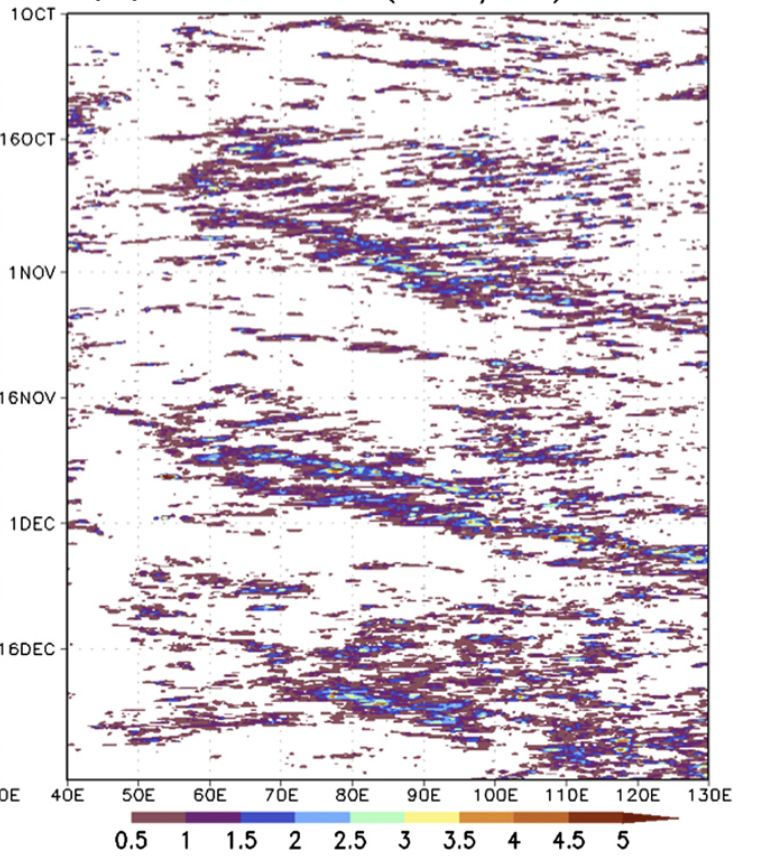

An easy way to understand wave dispersion is to plot the Hovmoller diagram of variables of interest in a longitude-time plane. (i.e., the figure below Fig. 16). If we track along a specific feature (let’s say ), the slope of that feature on the Hovmoller diagram represents one single dot on the space-time plot i.e., \((\omega,k)\) is a specific pair. One can also take Fourier transform twice (one along time and the other along longitude coordinate) of the Hovmoller diagram, the yielded result is also the space-time diagram.

Fig. 17 The meridional averaged precipitation from TRMM product during the DYNAMO field campaign.#

Vertical Normal Mode#

An important thing is (53) is scaled by \(C\) rather than \(C_0\) indicating that we still need to determine \(C\) to close the problem. According to the separation of variable, we know \(\frac{C_0^2}{C^2}=\lambda\) or \(C = \sqrt{\frac{C_0^2}{\lambda}}\). \(\lambda\) on the other hand represents the “ID” of a wave’s vertical structure. To see what \(\lambda\) stands for, we will complete the derivation of vertical normal mode.

Here we implement two boundary conditions. At \(p=p_s\) and \(p=p_t\), \(W(p)=0\), which represents the ridge-lid boundary condition. (one should notice that the lower boundary is not necessarily 0 given the frictional convergence plays a certain role in wave dynamics).

(61) is an Euler differential equation, which can be solved by assuming a solution form of \(W(p)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} C_n p^{n+r}\). Using this series solution, we can have

Substitute two boundary conditions into (62) we have

which implies \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}-\lambda}=\frac{i \pi m}{\mathrm{ln}(\frac{p_s}{p_t})}\) and \(B=-A p_t^{2\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}-\lambda}}\) (readers will complete the steps in the HW). The vertical structure solution can therefore be written as

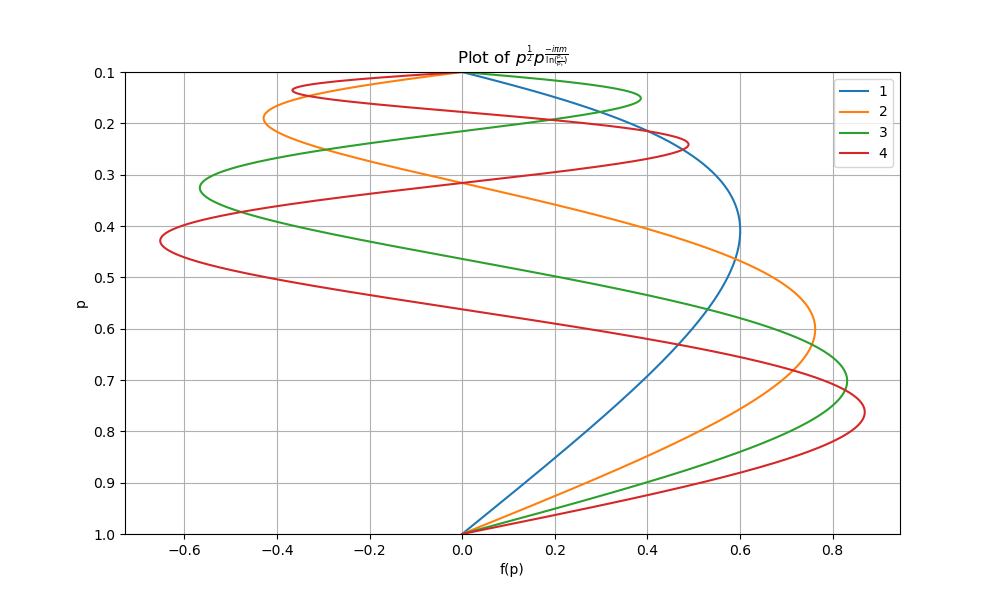

It is obvious that two basis functions constitute the vertical structure solution i.e., \(p^{\frac{1}{2}}p^{\frac{i\pi m}{\mathrm{ln}(\frac{p_s}{p_t})}}\) and \(p^{\frac{1}{2}}p^{\frac{-i\pi m}{\mathrm{ln}(\frac{p_s}{p_t})}}\). Results are plotted in the figure below

Fig. 18 The vertical normal mode for m=1,2,3,4#

Recall that \(\lambda = \frac{C_0^2}{C^2}\), also \(\frac{1}{4}-\lambda=-\frac{\pi^2 m^2}{(\mathrm{ln}(\frac{p_s}{p_t}))^2}\). Two equations lead to \(C^2=\frac{C_0^2}{\frac{1}{4}+\frac{\pi^2m^2}{(\mathrm{ln}(\frac{p_s}{p_t}))^2}}\).

It’s not hard to find that bigger \(m\) corresponds to a more complicated vertical structure and slower propagating speed. Indeed, higher \(m\) usually represents are more stratified fluid and therefore the density difference between two adjacent layers is smaller as well. Small density difference leads to more reduction in gravitational acceleration.

If one substitutes the non-dimension parameters with typical tropical conditions, we will have \(C_0\sim 76\frac{m}{s}\), \(C_1\sim 50\frac{m}{s}\), \(C_2\sim 26.2\frac{m}{s}\),… The first baroclinic structure has a wave speed around 50\(\frac{m}{s}\) which is much faster than the observed tropical wave phase speed. Madden-Julian oscillation (one of the dominant tropical variability), has a phase speed around 5-10\(\frac{m}{s}\) closer to the fourth baroclinic mode. MJO is, however, dominated by the first baroclinic mode structure. This inconsistency drives the community to study MJO in two different directions (1) the MJO is governed by wave dynamics with various vertical structures or (2) the MJO’s characteristic time sccales are determined by something else other than the internal timescales of free-wave solution. We will have a more in-depth discussion next week.

Convective Coupled Wave#

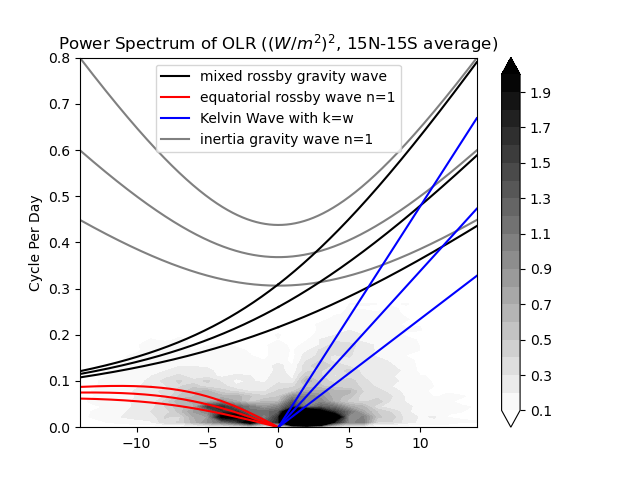

While (59) seems over-simplified (linear, resting basic states…), the observation is however closely tied to the analytical solution of tropical wave solution. The figure below shows the symmetric components of tropical OLR (averaged over 15\(^{\circ}\)N-15\(^{\circ}\)S). One can find two peaks stand out, one follows the dispersion relationship of Kelvin wave and the other one follows the equatorial Rossby waves. Given that OLR is a good proxy of convection, Fig. 19 suggests that the convectively coupled tropical waves to some degree can be considered as a forced response of free-wave solution, where the forcing time scales are either much shorter or equivalent to the internal time scales of free-wave solutions.

Fig. 19 The OLR power spectrum superimposed with the analytical dispersion relationship. The three curves (from top to bottom) for each type of wave correspond to different equivalent depths (50,25 and 12 meter).#

Another interesting but less addressed feature is the maximum around \(k=1-4\) and \(\text{CPD}\leq 0.05\) (i.e., period lower than 20 days). This is the famous Madden-Julian oscillation. Its distinct spectrum suggests the linear wave theory may not be able to explain the corresponding dynamics. Finding the governing equation for modeling MJO has been the Holy Grail in the scientific community of tropical large-scale dynamics. We will go through more debates in between different communities in the next week.